Digital Media in Clinical Trials

Compliance By Design

Authors: Allison Morgan BSc (Hons), Suzy Thorpe BSc (Hons), Hannah Leaper.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

In the context of clinical trials, clinical digital media assets consist of untraditional data sources and typically include videos, photographs or audio files taken during the clinical study period to support a variety of research purposes. Digital assets can also include transcribed participant interviews, which cannot be captured in databases.

Clinical digital media assets are increasingly being used by the biopharmaceutical industry across a wide range of diseases to support the evaluation of new therapeutics.

The future promise of progressively sophisticated AI is expected to offer even greater opportunities in automated evaluation of both clinic and home video and audio files, reducing participant burden and offering enhanced understanding of disease, for which the Biopharma sector needs to be ready.

Clinical digital assets are also valuable in supporting the clinical trial process, from evaluator training programmes and reliability testing to centralised quality control.

Importantly, clinical digital assets can bring traditional data to life, by demonstrating how numerical changes in form or function translate into tangible benefits for patients.

There is a clear emphasis on the patient experience by Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Health Technology Assessors (HTAs) in establishing what meaningful change looks and feels like when using validated data capture methods. Coupled with regulatory agency commitments to advancing digital health and evolving guidance on computerised systems, the use of clinical digital media in supporting registration programmes is predicted to follow its current trajectory of rapid and continued growth.

The widespread use of clinical digital assets comes with great responsibility and unique challenges in compliance, safeguarding patients and ensuring respect for their privacy.

We discuss the need for Compliance by Design in the context of clinical trials and how to achieve this.

USE OF CLINICAL DIGITAL ASSETS IN CLINICAL STUDIES

There are many reasons why digital assets may be required in clinical studies.

Efficacy, Safety and Diagnostic Evaluation

Clinical digital assets can be used in the standardised quantification of response to treatment across many diseases, including dermatological and ocular conditions. Similarly, qualitative evidence demonstrating the clinical relevance of numerical changes can be clearly observed through videos of improved mobility or function in neuromuscular conditions. Digital assets may also be used to assess and quantify off target effects, such as rashes or swelling, or used for central adjudication to confirm diagnosis or response to treatment.

Direct Patient Feedback

FDA and EMA have many initiatives to extend patient feedback beyond the classic data points in clinical trials to learn more about the meaning to patients of any changes observed. Audio and Video diaries can help evaluators understand how the patient feels about changes in response to treatment and also to side effects. Audio and Video diaries can also shed light on previously unknown side effects and benefits.

Exit Interviews

Regulators may mandate Exit Interviews at the end of a study, to understand the patient’s view of real-world benefit and side effects and further correlate this to the observed treatment effects.

Interviews are typically audio recorded to enable specialist central evaluators to assess consistent themes that arise from patients, where words, word frequency, tone of voice and cultural contexts may be used to express the same feelings between patients in different ways.

Inter and Intra-Rater Reliability Testing

Regulatory Agencies often mandate that inter and intra-rater reliability testing is conducted for critical outcomes, to ensure that all assessors are operating to the required specifications and is reproducible between and within assessors to consistently achieve the same result. An example of this may be to oversee the conduct of functional timed tests or use of a medical device. Videos can support the reliability testing process and provide evidence to regulators.

Training and Quality Control

Video assessments may also be used to QC evaluations, ensuring adherence to pre-specified methods. This also allows rapid response to site specific training needs, or identifying assessment challenges with the study population where process may need to be adapted.

DIGNITY MATTERS WITH DIGITAL ASSETS

Enhancing the patient voice comes with its own unique challenges. The industry has always been a frontrunner in protecting personal clinical information through the use of secure clinical databases, use of unique identifiers and stringent adherence to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) – well before General Data protection Regulation (GDPR) legislation was ever in place.

It’s hard to believe that even today, some digital assets in clinical trials are being stored on USB drives, local hard drives, smartphones or cameras without stringent long term ‘lock and key’, archive or authorised access procedures. Assets are still being transferred via emails and unvalidated generic web portals with broad user access and no restrictions on downloading, editing, forwarding or deleting. Some are still even being sent by post.

For some assessments, there may be modesty concerns with some video assessments, for example where hip or shoulder manipulation is required revealing other parts of the anatomy, or there may be self-consciousness where a participant is in a state of partial undress or embarrassed by their condition.

Similarly, audio and video files may reveal personal and private information, or record participants in a vulnerable or distressed state.

CONFIDENTIALITY IS KEY

Unlike other digital assets such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan (MRIs) and ultrasounds, participant data captured by video, audio and photographic modalities may more readily identify study participants and may also contain highly sensitive personal information.

In addition to preserving modesty and dignity at all times, the procedures applied when using digital assets must also avoid participant identification. The recording of the face is an obvious example of the potential for participant identification, however tattoos, scars or other unique physical traits may also identify the participant. Even jewellery may reveal a person’s identity.

The same considerations for privacy must also be applied to assessors and other study personnel who may be captured on video or audio files, such as referring to someone by name, or capturing an image of a hospital identification tag.

Study participants expect and trust that their data will be transmitted in a secure manner, with maximum restrictions on access. Every effort must be made to ensure this across every aspect of the study, not just within the traditional clinical database.

Importantly, measures must also be in place to address any identifiable features captured, which will inevitably occur from time to time, through strict digital asset access protocols, systematic asset monitoring and de-identification procedures, such as image blurring and audio editing.

Transcribers of audio information must also be trained to de-identify personal information of both participants and study personnel and ensure secure digital methods are in place.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS WITH DIGITAL ASSETS

It is the role of Ethics Committees (EC) and Institutional Review Board (IRB) to protect the patient’s privacy and dignity, as well as their overall understanding and wellbeing. ECs and IRB now rightly ask for detailed procedures regarding acquisition, transmission, storage, access and management rights of digital assets. They want to know exactly who will be looking at the data and for what purpose. Responses to questions along the lines of ‘stored in a password protected portal’ are increasingly seen as insufficient. The chain of custody and security at each step must be described and be compliant with GDPR and ideally 21CFRPart11. ‘Off-the-shelf’ file sharing platforms are rarely fit for purpose.

Similarly, widespread access to clinical digital assets by entire Sponsor teams, where items may deliberately or inadvertently be used beyond the pre-specified and intended purpose defined in the protocol, is considered unacceptable.

Concerns have also been expressed by ethical reviewers regarding the local institutional storage of digital assets in a GDPR compliant manner and in the absence of robust ‘lock and key’ protocols, have instead insisted on detailed instructions for file deletion before granting approval for the study. Consent is of course a critical part of the process and must be in place prior to any video, audio or photographic data collection. It is important that the participants fully understand what will be involved, how their data will be used, transmitted and stored and who will be looking at it through detailed patient information and informed consent – a legally binding document for the Sponsor. Anything beyond the intended purpose is not allowed. In many cases, an additional signature line on the informed consent form is required to ensure the participant specifically agrees to this aspect of the study.

CLINICAL DIGITAL ASSET TRANSFER: THE CHALLENGES OF CLOSED AND OPEN SYSTEMS

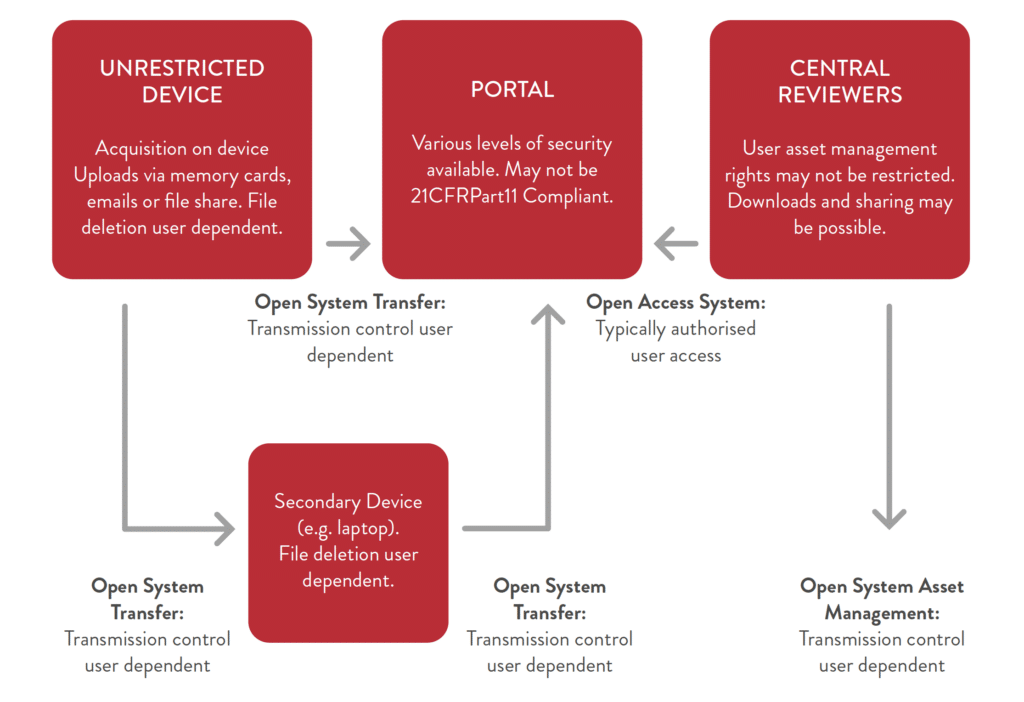

Ideally, all clinical digital asset transactions should take place within a closed system, to prevent the transmission or use of assets in a non-compliant manner, however many clinical trials still employ digital asset transfer systems where some or all parts of the system are ‘open’. In other words, the control of access, downloading and sharing is dependent on the user. This approach inevitably introduces an element of data protection risk, often inadvertently.

Downloading a copy onto a local laptop in order to view or transmit to another machine for example, will leave a trail of the patient’s information, unless laborious measures are taken in real time to retrace the digital steps and ensure total deletion. Even then, digital copies may still be retrievable.

The risk of multiple unauthorised copies is high. A typical open system highlighting the areas of user dependency is depicted in Figure 1 below:

OPEN SYSTEM TRANSFER:

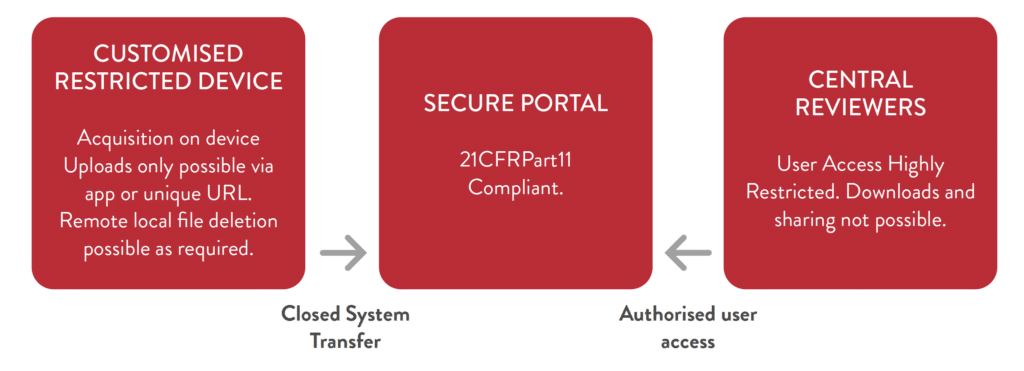

While a perfectly closed digital asset management system is not always possible, especially when specialist equipment must be used to acquire the image or audio, every attempt should be made to close as many parts of the system as possible.

Overcoming user dependent areas of risk can increase data protection and at the same time minimise burden to investigative sites, central review teams and the sponsor through simplified, highly secure digital acquisition, transfer, review and storage procedures.

A fully closed system controls user access and asset management rights end-to-end, with no possibility to work outside of the system. A closed system is the easiest to use and provides maximum security for participant data.

Figure 2 shows the economical workflow and data security of a closed system:

CLOSED SYSTEM TRANSFER:

In all instances, clear and detailed documentation and training programmes regarding the digital data flow, access, review and deletion procedures must be in place for all study personnel, with clear evidence and reminder of training. Clinical Monitors should check that the appropriate procedures are being adhered to during their monitoring visits.

Finally, archived digital assets should have clear ‘lock and key’ procedures, whether stored digitally or on hard drives, so that access remains highly restricted and is also not dependent on the user.

DO’S AND DON’TS OF CLINICAL DIGITAL MEDIA MANAGEMENT: COMPLIANCE BY DESIGN

DO:

- Determine how digital data will be captured and how it will be standardised for the study.

- Define who should have access and why.

- Investigate institutional firewalls and other technical barriers as early as possible.

- Map out the entire acquisition, transfer, storage, access and archiving pathway as early as possible.

- Provide clear instructions and training on digital data security.

- Be prepared to answer detailed questions from ECs and IRBs regarding digital data security and data access.

- Think about long term digital archiving, locking and unlocking procedures, including ‘lock and key’ security which applies to both digitally stored data and separate hard drives. Do consider cloud based storage solutions with stringent access protocols.

DON’T:

- Don’t assume that all locally available devices will provide the same data quality, or consistent data across the study.

- Don’t think that consent means that company wide access is allowed – it must always be in keeping with the predefined purpose of the protocol.

- Don’t assume that the hospital can access all external portals and websites or are able to upload files

- Don’t assume that password protected open system transfers are compliant or secure.

- Don’t assume that study teams will store local copies in a GDPR compliant manner, or delete all local copies.

- Don’t provide one-line answers to IRBs and ECs regarding complex data security issues and expect them to be reassured.

- Don’t assume that data archived on portable hard drives will be accessible or usable in the future. Dormant discs can become corrupted and technology moves on.

HOW TO SELECT A DIGITAL ASSET MANAGEMENT PARTNER

It is critical that any digital asset partner meets the following minimum requirements:

- GAMP5 validated system

- CRF21Part11 compliant

- ISO 27001 / SOC 2 compliant system

- Strong access control, following the principle of least privilege

- Procedures for disaster recovery and backup

- End-to-end and data-at-rest encryption

- Capability to collect standardised metadata for digital assets

- Extensive support for viewing a wide range of digital media formats

- Comprehensive audit trail

- Materials for training site personnel and end users

- User-friendly interface that reduces barriers for clinicians to adopt and responsive HelpDesk

- Sites provided with a secure and restricted data capture device

- Firewalls between clinical studies and investigative sites

- Systematic audio and video de-identification PII capabilities

- Export to secure end-of-trial data or long-term digital archiving in a secure manner

- Clearly defined ’Lock and Key’ archiving protocols

CONCLUSION

Digital clinical asset management is a critical aspect of clinical research that must not be overlooked. It is important to ensure that the methods of digital data capture are credible and usable, especially with a stream of new regulatory agency guidances and initiatives to elevate the importance of the patient experience in drug and device evaluation.

To achieve this, it is essential that Compliance by Design is prospectively encompassed in the clinical asset management process. This should involve engaging specialist vendors with their technical knowledge early in the process to assist with the study structure, documentation, and workflow.

It is also important to note that protecting clinical digital data is the responsibility of all parties involved in the study, including site study personnel, CROs, specialist vendors, and the sponsor. All parties should be actively engaged from the outset to ensure a secure chain of custody for the asset and enhance participant protection.

Fortunately, technology now gives us the ability to handle sensitive clinical digital assets in a robust manner and comply with 21CFRPart11 and GDPR regulations. Partnering with digital clinical media management partners who offer centralised end-to-end control is an effective way to ensure reliable and valid media-based datasets in support of clinical registration programs. By doing so, we can ensure that the patient experience is elevated and that clinical research is conducted with the highest standards of quality and compliance.

REFERENCES

- Asan O, Montague E. Using video-based observation research methods in primary care health encounters to evaluate complex interactions. Inform Prim Care. 2014;21(4):161-doi: 10.14236/jhi.v21i4.72. PMID: 25479346; PMCID: PMC4350928

- Bhattacharya S. Clinical photography and our responsibilities. Indian J Plast Surg. 2014 Sep-Dec;47(3):277-80. doi: 10.4103/0970- 0358.146569. PMID: 25593409; PMCID: PMC4292101.

- Davies, E.H., Matthews, C., Merlet, A. et al. Time to See the Difference: Video Capture for Patient-Centered Clinical Trials. Patient 15, 389–397 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40271-021-00569-1

- European Medicines Agency, Patient experience data in EU medicines development and regulatory decision-making, Outcome of the workshop on 21st September 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/executive-summary-patient-experience-dataeu-medicines-development-regulatory-decisionmaking_en.pdf

- EMA, Guideline on computerised systems and electronic data in clinical trials, 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/guidelinecomputerised-systems-electronic-data-clinicaltrials_en.pdf

- Eastern Research Group, Assessment of the Use of Patient Experience Data in Regulatory Decision-Making, , 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/150405/download

- FDA Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance Series for Enhancing the Incorporation of the Patient’s Voice in Medical Product Development and Regulatory Decision Making 06APR2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapproval-process-drugs/fda-patient-focuseddrug-development-guidance-series-enhancingincorporation-patients-voice-medical

- FDA, Patient-Focused Drug Development: Methods to Identify What Is Important to Patients Guidance for Industry, Food and Drug Administration Staff, and Other Stakeholders, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/131230/download

- FDA, Digital Health Center of Excellence, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digitalhealth-center-excellence

- GDPR: General Data Protection Regulation https://gdpr-info.eu

- Lakeland, EU Perspectives: Guidance for Using Patient Experience Data in Real-World Studies, Applied Clinical Trials, May 2023.

https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/eu-perspectives-guidance-for-using-patientexperience-data-in-real-world-studies - Parry, Acceptability and design of video-based research on healthcare communication: Evidence and recommendations, Patient Education and Counseling, Volume 99, Issue 8, 2016, Pages 1271-1284, ISSN 0738-3991, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.013. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738399116301173)

- Patient Focused Medicines Development, Highlighting Recent Trends in the Fast-Evolving Patient Engagement and Patient Experience Landscape, 2021. https://patientfocusedmedicine.org/docs/Trendsin-the-Fast-Evolving-PE-PED-Landscape.pdf